Planet & People

Facing the Anthropocene era, where human activity has become the dominant force shaping the planet, the notion of separating humans from nature – rooted in modern, Western industrial civilization – is no longer tenable.

The global demand for smartphones, electric vehicles, and renewable energy technologies has skyrocketed, leading to a relentless pursuit of cobalt deep beneath the earth.

Siddharth Kara in Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives

Deep mining of lithium and cobalt, particularly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), poses significant ethical and environmental challenges in technology production, impacting everything from common batteries to electric vehicles (EVs). The DRC supplies over 70% of the world’s cobalt, a critical component in lithium-ion batteries used in consumer electronics and EVs (Shedd et al., 2017). However, reports from human rights organizations, such as Amnesty International, reveal widespread modern slavery and forced labor in Congolese mines, where miners, including children, work under extreme and inhumane conditions without protective gear. This puts them at risk of severe health issues due to prolonged exposure to toxic substances and hazardous mining environments (Amnesty International, 2016). Major industry companies frequently obscure the truth about these conditions, citing complex supply chains as a barrier to full transparency and accountability (Kara, 2018).

The environmental impact of cobalt and lithium mining further exacerbates these human rights abuses. The extraction processes result in significant ecological disruption, including soil degradation, deforestation, and water pollution, which destabilize local ecosystems and contribute to global environmental imbalances (Ali et al., 2017). These practices worsen climate change by releasing carbon stored in vegetation and soils and by reducing biodiversity that plays a crucial role in climate regulation. Moreover, the demand-driven exploitation of mineral-rich regions fosters geopolitical instability and perpetuates cycles of poverty and exploitation in countries like the DRC, where wealth from natural resources fails to translate into local economic development (World Bank, 2020.

Circular economy practices, with an emphasis on reuse and sufficiency, help alleviate some of the pressure on new mineral extraction, thereby reducing the negative impact on ecosystems and human rights. Foxway contributes to this effort by extending the life of technology through refurbishment and reuse, promoting a sustaianble model that lessens reliance on new resource extraction and helps reduce the demand for conflict minerals. To address these broader issues, it is also crucial to enforce ethical mining practices, increase transparency in supply chains, and invest in technologies that reduce dependency on conflict minerals, thereby promoting both environmental sustainability and social justice.

Governance & Corruption

The extraction and exploitation of resources in the Global South to meet the technological demands of the Global North illustrate a significant imbalance in global economic structures.

In today's global corporate landscape, initiatives like the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI) serve as trusted frameworks for ensuring ethical sourcing of minerals. However, it is important to remain critical, as not all information provided is entirely transparent or beyond scrutiny.

While the RMI plays a crucial role in promoting responsible practices, there are still significant concerns that warrant deeper examination. As we navigate these complex times, questioning the efficacy and comprehensiveness of such initiatives becomes vital to genuinely tackle the ethical challenges present in the global supply chain.

“They tell the international community about their programs in Congo and how the cobalt is clean, and this allows their constituents to say everything is okay. Actually, this makes the situation worse because the companies will say-"GBA assures us the situation is good. RMI says the cobalt is clean." Because of this, no one tries to improve the conditions.“

(…) “To this day, I never met anyone associated with the GBA or the RMI in the Congo, nor did I ever hear about any inspections of artisanal mining areas from any colleagues in the DRC being conducted under their banners. (…) "According to the OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development], up to seventy percent of the cobalt from the DR Congo as some touch with child labor. There are large gaps of information the supply chain, so we have to fix the information flow in a trusted way.”

Siddharth Kara in Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives

While wealth and technological advancements accumulate in developed nations, resource-rich developing countries often suffer from environmental degradation and social injustices.

This imbalance is perpetuated by governance corruption, where local elites and multinational corporations profit while the broader population bears the brunt of exploitation (Escobar, 1995). The lack of transparency in global supply chains makes it difficult to hold companies accountable for unethical practices, as complex networks of subsidiaries and third-party suppliers obscure the true origins of materials and labor conditions (Seay, 2012). This situation challenges notions of global justice and equity, raising philosophical questions about the ethical responsibilities of consumers and corporations in affluent nations (Pogge, 2008). As Auty (2001) highlights in his research on resource-rich countries, the "resource curse" often manifests when corrupt governance structures prioritize short-term economic gains over sustainable development, leaving local communities impoverished and ecosystems devastated.

This opacity is compounded by inadequate regulatory oversight and enforcement, enabling corporations to evade scrutiny and mask the true environmental and social costs of their operations. As noted by Seay (2012), the complexity of global supply chains and the prevalence of corruption create significant barriers to achieving transparency and accountability in the technology sector. This situation not only undermines efforts to promote sustainable and equitable resource use but also perpetuates a cycle of exploitation and environmental degradation that disproportionately affects vulnerable populations in developing countries. Addressing these issues requires a concerted effort from governments, corporations, and civil society to enhance transparency, strengthen regulatory frameworks, and prioritize ethical and sustainable practices in the technology industry.

Governance corruption in technology production is a pervasive issue that often remains hidden by governments, politicians, and global tech companies. This lack of transparency leads to the exploitation of both natural resources and people, without adequate accountability. The technology industry relies heavily on critical minerals such as cobalt, lithium, and rare earth elements, which are primarily sourced from resource - rich regions in the Global South.

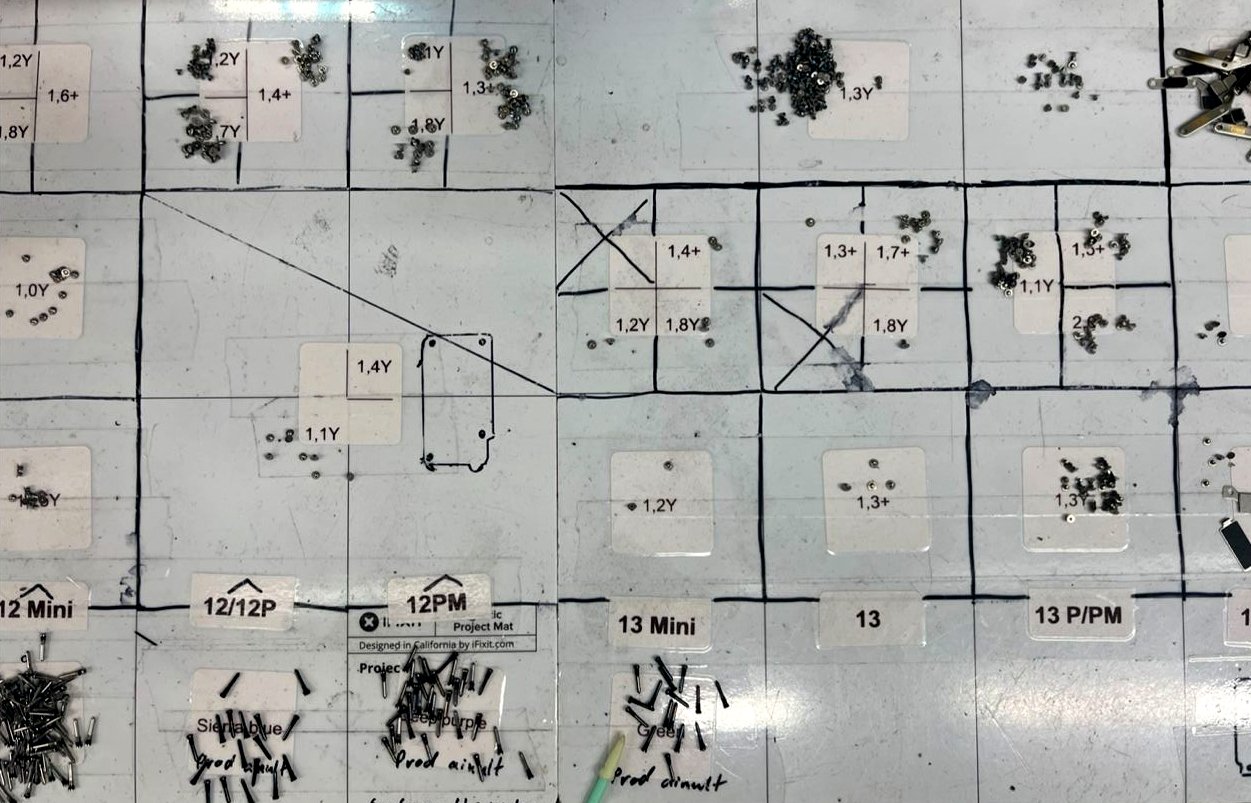

In smartphone manufacturing, the intentional use of screws with millimetrical differences in size is a subtle yet deliberate tactic that contributes to the device's eventual self-destruction, breaking the structure while trying to dismantle it. This design choice complicates the disassembly and repair process, making it nearly impossible to fix or recycle the phone without highly sophisticated technology, typically available only in the Global North. By creating such barriers, manufacturers effectively limit the lifespan of the devices and restrict access to repair options, exacerbating electronic waste and deepening the divide between regions with advanced technological capabilities and those without. This practice not only undermines sustainability efforts but also perpetuates economic and environmental inequalities on a global scale.